The Louisville Unions Rediscovered

By Bailey Mazik, Curatorial Specialist

Step back in time with me, to the spring of 1908.

Teddy Roosevelt is president.

The first model-T hits the streets in a few months.

Your hometown of Louisville is gearing up for the 34th running of the Kentucky Derby.

And, thankfully, there are many opportunities to watch baseball games at all levels of competitiveness.

Now let’s briefly jump ahead 110 years, to June 2018. Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory just acquired two special photographs. They both show baseball players on a field, posed to look like action shots. The information that accompanied the prints guessed that the players were from the Louisville White Sox, a Negro Leagues team in 1931. So, while processing these photographs I took this information into consideration but, as Curatorial Specialist, I always verify details so we can be certain of accuracy.

It’s incredibly rewarding for me to research our archives and find meaningful connections that enhance understanding about our company, the city of Louisville, and the countless number of people that baseball has brought together. I examine records, documents, and objects and ensure that we know what we have, where it came from, and why it’s important that we have it. Often, it’s straightforward to connect the dots, thanks to the work done by baseball historians through the decades. But original research can be quite tedious because information is often lost or not well preserved through the years. Sometimes the connections I work so hard to find cannot be backed up by evidence. But other times, all the attention to detail, examining every possible aspect, searching from every angle for information pays off in a big way.

And this is, perhaps, my most rewarding discovery yet.

Upon receiving these photographs, I was immediately eager to connect the dots. Who are these men? Where were these photographs taken? Are there other photographs of this team? Did the players leave journals behind? These questions were circulating in my head as my eyes landed on the big “L U” letters embroidered on their uniforms.

Hmmm; if this was the “White Sox” team as previously predicated, the uniforms would probably include the letters “W S,” instead of “L U.” So, I knew to look for a team that was not the White Sox.

The next important clue was noticing the Sunny Brook Distillery Co. building in the background of one of the images. A location is very helpful in identifying both a specific team and its playing field. And the most exciting bit of information is a faint inscription on the back of one of the photos that is dated February 22, 1909, long before 1931. See scans of this below:

Original Scan

Enhanced Scan

I enhanced the scan of the back of the photo to remove all color and increased the contrast which helped me pull out a little more detail in the faint handwriting.

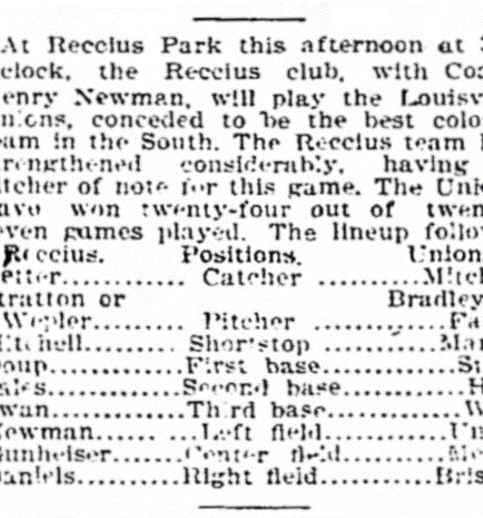

Now I had the initials “L U,” a location in town, and I decided to start searching in the 1908 timeframe, the season before February 1909. I was on my way! My next step was to search through a database of digitized newspapers; an incredible resource of information. After poring over 1908 articles from the Louisville Courier-Journal, I discovered that these are images of players from the Louisville Unions team, a semi-professional, “colored” (as referred to in articles from the time) baseball team. According to many articles from the spring and summer of 1908, the Unions team played other semi-professional and amateur teams, from Louisville and elsewhere. Their local opponents included the Louisville Giants, Reccius Club, and City League Stars. Teams from other states included Ohio, Tennessee, Indiana, Pennsylvania and New York.

I didn’t have to read for very long before learning that the Louisville Unions were quite a team! They reportedly won 24 out of 27 games this 1908 season. Most of these matches, the Louisville Unions simply outplayed their competitors, as emphasized by this Louisville Courier-Journal article on July 12, 1908:

“At Reccius Park this afternoon at 3:15 o’clock, the Reccius club, with Coach Henry Newman, will play the Louisville Unions, conceded to be the best colored team in the South.”

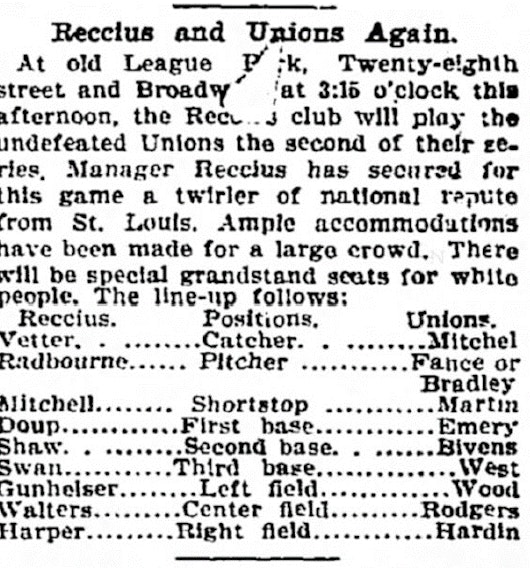

This successful team had its own playing field located at 28th Street and Broadway. In 1908 newspaper articles, this field is referred to as either “Unions’ Park” or “old League Park”; it is also known as Eclipse Park II. About 15 years earlier in 1893, this field was formed into a sort of complex for the Louisville Colonels team, where Honus Wagner hit his first professional home run in 1897.

The 13-acre plot consisted of a full-size field for the Colonels to play on, a smaller field for amateur teams, bike paths, and picnic areas, and was enclosed by a wooden fence. This was in the residential neighborhood of Parkland and was intended to serve the community in a variety of ways. The Colonels played here for 6 years until an electrical storm caused a fire and rendered the field and stands unusable for the professional National League team after the 1899 season. This didn’t matter much anyway, because in 1900 the Colonels ceased to exist when the National League downsized from twelve teams to eight, and cut Louisville from the league.

Colonels’ owner Barney Dreyfuss took over the Pittsburgh club and relocated a number of Louisville’s best players to the Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1908, after repairs were made, the Unions team was based at this historically important lot.

Although the Unions had a home base and the team’s season was covered in the city’s newspaper, racism was rampant. In Jim Crow-era Louisville, segregation was upheld and legally enforced in nearly all facets of life including schools, transportation, healthcare, and marriage.

But black people and white people could meet on the diamond and play baseball against each other.

This racial dichotomy is reinforced in articles that included something like this: “Grandstand reserved for white people.” See an example from June 14, 1908, below:

“There will be special grandstand seats for white people.”

There’s a rich history of black baseball teams of various levels (recreation, semi-professional, and professional) in Louisville besides the Louisville Unions, Louisville Giants, and Louisville Stars. For example, an article from June 7, 1886 summarizes a tight game between Falls Citys and Old Honestys, playing at “their park near Sixteenth Street and Magnolia Avenue.” Falls Citys kicked it into gear in the eighth inning to pull off a win. And on May 30, 1907 the Post-office Boys and “the colored team of the YMCA” played each other in what was expected to be a “hotly contested” game.

Baseball was so important here during this time that in April 1908, Louisville hosted a meeting for the proposal of the National Colored Baseball League. Leaders from Louisville, along with those from other cities including St. Louis, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Columbus, Cleveland, and Nashville met with plans to form this league. This was backed financially by white and black sportsmen and Louisville’s team was to be backed by a stock company. Disappointingly, the league was voted “impracticable” and promptly dropped.

The Louisville Unions team also dissolved after the 1908 season. Curiously, there’s no mention of them before or after 1908, which fits with why one of our photos is marked “February 1909.” Perhaps whoever wrote that was commemorating the team and its only season that wrapped up a few months before in 1908. On the back of the photograph showing a player sliding into a base, in addition to the date, I can make out the phrase: “Charles is a sleep [sic].” Better scanning and technology would help us to read more of the inscription and lead to better information about the team.

A cohesive league, like the one proposed in 1908, wouldn’t be formed for another 12 years. The Negro National League ran from 1920-1931, followed by the Negro American League from 1937-1962. Louisville had teams in both leagues: Louisville White Sox (1931), Louisville Buckeyes (1949), and Louisville Clippers (1954). Of course, Jackie Robinson broke the MLB color barrier in 1947 but integration was a slow process.

I’ve been thrilled to learn about the Louisville Unions and their role during this important chapter of baseball and American history. I feel lucky to have these photographs in our archives and I’m excited by the possibility of learning more about them!

Editor's Note –

The Louisville Unions Rediscovered exhibit will be on display into 2021.

In our collection we have bat records and correspondence with Negro Leagues legends like Oscar Charleston, Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, and Buck Leonard. We also have bats used by two of the game’s trailblazers. One is perhaps the earliest Jackie Robinson bat, dating to his playing days before breaking the color barrier in 1947. The other bat was used by Larry Doby in the 1954 World Series, seven years after breaking the American League’s color barrier.