Finishing Touches: Reds Legend George Foster and His Louisville Slugger Legacy

By John Hughes

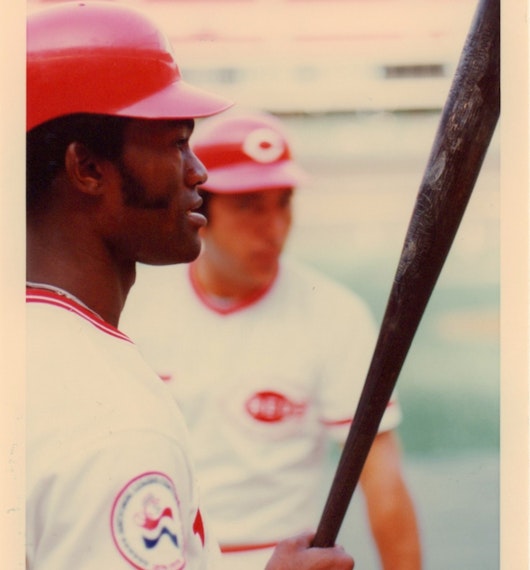

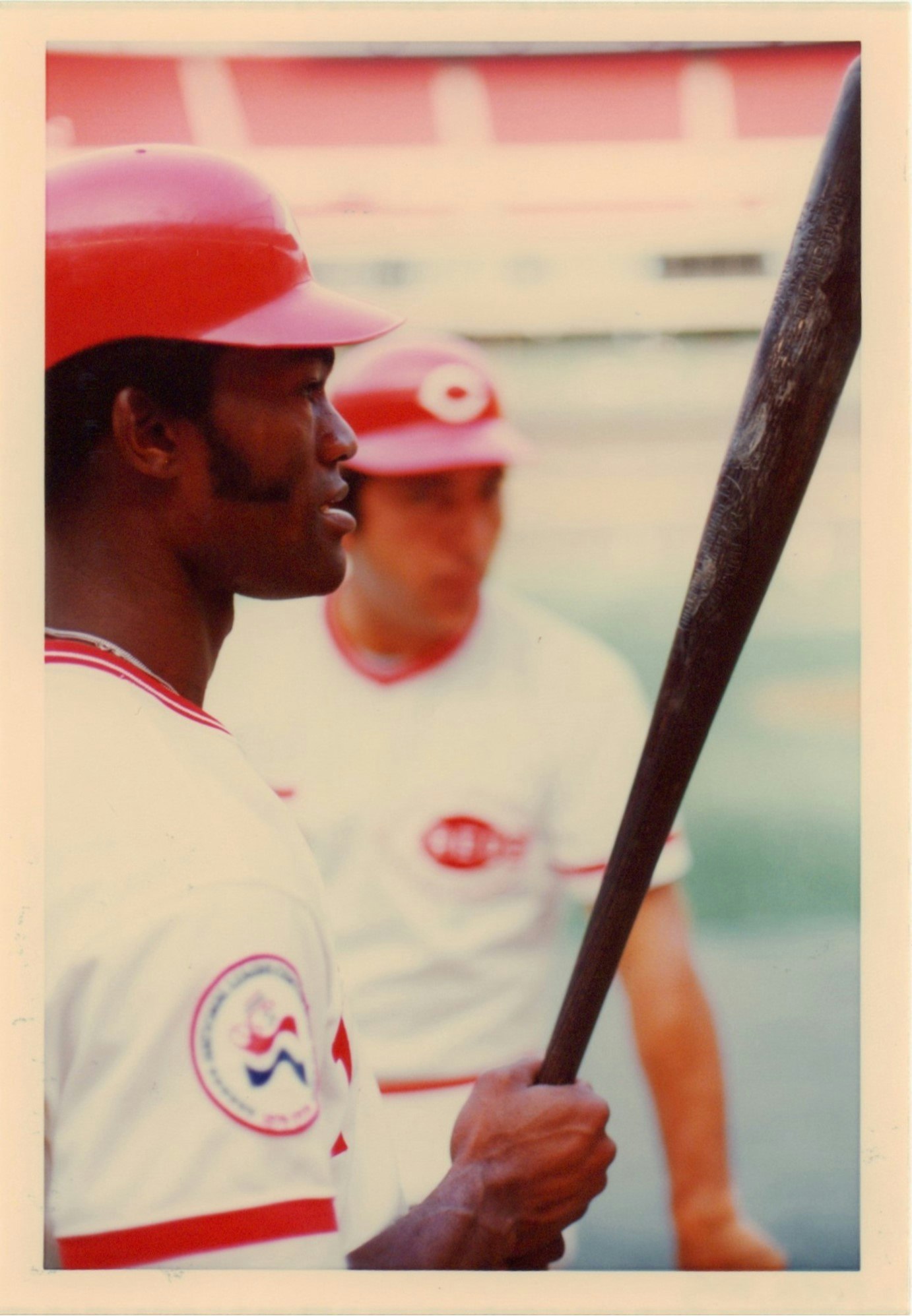

George Foster, a legend of 1970s Cincinnati Reds’ dominance, sits in the Hillerich & Bradsby Co. (H&B) Archive Room and talks about how he swung his Louisville Slugger.

How he swung it to two World Championships; to National League MVP (1977); to NL MVP runnerup (1976); to two-time NL Home Run Leader and three-time RBI Leader; to a 1981 Silver Slugger recipient; and how he swung it that 1977 season to clobber 53 homers and push home 149 RBI.

At age 70, Foster looks fit enough to do more than just talk The Game. These days, though, he’s using his extraordinary baseball experience to shape young ballplayers. Coaching his “Foster’s Force” team recently brought him to a tournament in Louisville and to a tour of the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory.

And when he speaks of hitting, Foster is fluent in the language typical to those who know how to hit; but a lingo apt to confound those of us for whom the concept of “seeing, centering, smoking” a baseball is more foreign than any Rosetta Stone could ever translate.

George Foster, for example, says that to be successful hitting, a person should “throw the knob” (of the bat) at the ball.

Wait a minute, George. All those years on dusty fields chattering “Hey Batter, Batter, ssssswing Batter!” we should have been haranguing our opponent with “Hey Batter, Batter, throoooow Batter!” Well, not really. But:

“When you swing the bat, it’s more like you’re pushing the barrel through the zone,” Foster says. But if you “throw the knob” you “get inside the ball, which gives you more time to wait."

Foster also talks about “hitting through the ball” and “hitting around the ball."

Think about that for a minute.

This roughly nine-inch sphere is hurling toward a 2.61-inch sphere and the person trying to tender a meeting of the two has approximately .25 seconds to introduce Mr. Ball to Mr. Bat.

And before stats such as “launch angle” and “exit velocity” mutated the language of hitting, great hitters talked about “hitting the top half” of the ball. Really? Can any of us imagine THAT as an objective, slinking back to the dugout saying “My bad, coach, I messed up and hit the bottom half of that 95-mile per hour pitch?!"

For most of us, “hitting through” or “hitting around”, is a degree of precision never experienced by mortals who would happily settle for “getting a piece of it."

But that’s the difference between us and The Greats. Of which George Foster was one.

In 1976, the left fielder hit 29 homeruns and led the NL with 121 RBI. Not too shabby. But in 1977, Foster played in 159 of the Reds’ 162 games and he was, well, Red(s) hot. 1977 was a magical outburst. His 53 HRs and 149 RBI happened in a season when, Foster says “it would seem (to him) all the parks were so small...”

Players today call it “being in the zone”. George Foster calls it the result of off-season preparation. “I came into that season in the best shape of my life,” he says. And not just his 6’1”, 180 physique. During the offseason, Foster practiced martial arts to improve his concentration. The result:

“The baseball looked like a balloon,” he says.

Today, Foster concentrates on development of young players, such as his Foster’s Force team.

The Force is among teams organized as part of Major League Baseball’s Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) program, where the connection is baseball, but the lessons are also about life. “They may or may not play baseball (as adults),” Foster says. “We try to develop them. You never know what they’re going to take with them.”

Foster says his involvement with youth baseball is a payback to his coming up, when San Francisco Giants scout George Genovese helped prepare him for his pro career.

“My scout would show up every day after school and walk us to the ballpark,” Foster recalls. “Soft toss (a hand-eye training drill) was a foreign thing, but he did it with me. He really believed in me...”

Foster made believers of baseball fans on his way to World Series rings in 1975-76 with the Reds. But it would be a few years later, with the New York Mets, that Foster would become part of baseball lore – not because of the way he finished, but because of the finish on his Louisville Slugger.

In the early 1980s, MLB players were attracted to, and TV commentators were fascinated by, the finish on Foster’s P72 Louisville Slugger.

The bat was black. Well, dark anyway, but looked black, at a time before today’s multi-colored bats and when the primary “color” was natural – at least in the minds of most fans. A non-natural finish was not unusual to players of the time, and in fact two-toned bats had been around since, at least, the 1950s and Harry “the Hat” Walker’s black and wine-colored Slugger.

But in the early 1980s – as a New York Met – Foster liked to joke that he had “integrated” bats by using a black one.

In fact, the bat was a deep hickory finish. But on television, the bat looked black. And particularly dramatic, because unlike natural-finish bats, it was solidly dark, so much so that the color obscured the famous H&B Louisville Slugger logo.

The “black” bat became known as the “Foster Finish." And while it became famous because of who used it, the reason for its name may have more to do with timing. Foster used it at a time when cable television suddenly and thoroughly flooded the airwaves with baseball games.

The hickory-over-flame-tempered “Foster” finish could rightly be called the “King” finish. Here’s the backstory: While playing Minor League ball in Indianapolis in 1973, Foster was teammates with another prospect, Harold “Hal” King. Foster had used up all his bats and – this being the Minor Leagues, where players pay for their own bats – asked King to loan him one.

H&B archives show that, in 1973, Hal King had indeed ordered flame-tempered, hickory finished P72s.

Foster liked King’s bat and, more significantly, was good with it (career average of 33 HRs and 107 RBI per season).

And with numbers like his in a city like New York in a time when mass consumption media was blossoming, well – sorry Hal King – say hello to the “Foster Finish."

While the viewing public might have seen the “Foster Finish” Louisville Slugger as a novelty, baseball players soon learned of its strategic value...

In the 1980s, sports stadiums’ lighting was moving out of the shadows – in part to accommodate the presence of added and higher-speed cameras – but did not nearly produce the bright-as-the-sun atmosphere of today’s fields. This condition was an advantage to a player swinging a dark bat on a dark night in a dark(er) stadium.

George Foster learned this not while at bat, but while in left field. “I used to time my jump (toward tracing a fly ball), by watching the angle of the bat coming through the zone,” Foster recalled. “But when a player used the ‘black’ bat I realized I couldn’t read the swing as well.”

Fielders had trouble seeing the ball come off the bat. This made the “Foster Finish” popular with hitters. But: Viewers had trouble seeing the H&B Louisville Slugger logo because the burn-branded logo was filled with dark paint. This made the finish decidedly unpopular with marketing specialists.

The finish that should have been called “King” but became “Foster” was discontinued by H&B – an early casualty of the product placement and “messaging” wars, as those marketing concepts were emerging to, today, dominate what we see and read and . . . buy.

George Foster retired from pro baseball in 1986. Others have/will hit more homers, drive in more runs, etc. But none will do it with the finish that will always be part of the great outfielder’s legacy. For the “Foster Finish” – flashy for its time, but dull in the media marketing spotlight – was retired, too. For awhile...

H&B brought back the Foster Finish in 2003, a year after the World Series was broadcast in high-definition for the first time, making it easier to see the famous Slugger logo even if obscured by the darkened branding.

And the first player to order one is now the manager of Foster’s old team, the Reds – David Bell. Bell played for the Philadelphia Phillies then and, as with Foster’s experience, his teammates liked the bat so much that several also ordered it.

But with fewer players using ash bats (the only wood that can properly handle burn branding) and more creative finishes becoming available, the last Foster Finish bat was ordered, by Texas Ranger Josh Wilson in 2014.